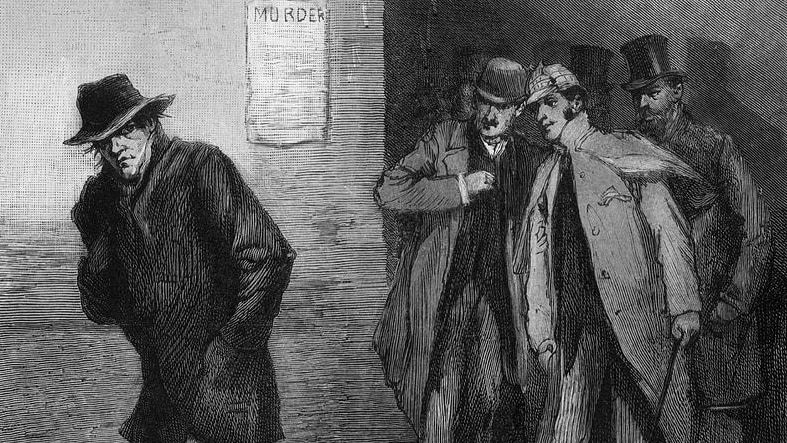

Jack the Ripper, without question, stands as the most infamous serial killer in history. The grisly tale of the twisted murderer who haunted the fog-choked streets of London in the late 1800s is one we all know. We’ve watched the films and read the books. We are well-versed in the chilling account of the killer who slashed the throats and mutilated the bodies of five victims. But there’s a part of the story that remains largely overlooked. And it’s the connection between the murders and a man named Montague John Druitt.

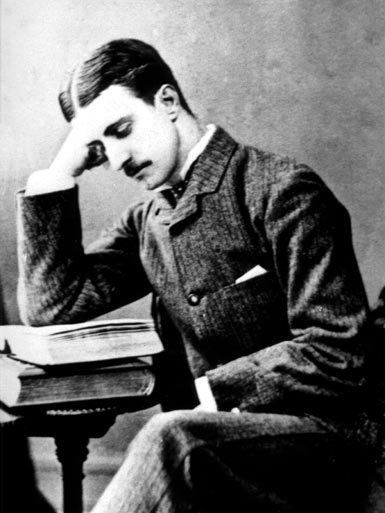

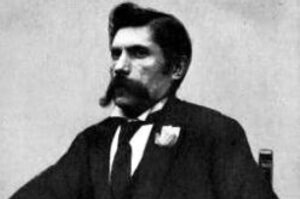

An Oxford graduate and respectable cricketer, Druitt’s bloated body was discovered floating in the River Thames New Year’s Eve 1888. His pockets were filled with stones to weigh him down to the river’s bottom. And a train ticket was found nearby. Was this mysterious death merely a coincidence? Or does it hold the key to understanding the identity of Jack the Ripper?

This is the premise of Deadly Overs, a podcast that delves into the dark intersections of murder and cricket. In Episode One, we explore the chilling connection between the unsolved crimes of the Ripper and the untimely death of Montague John Druitt.

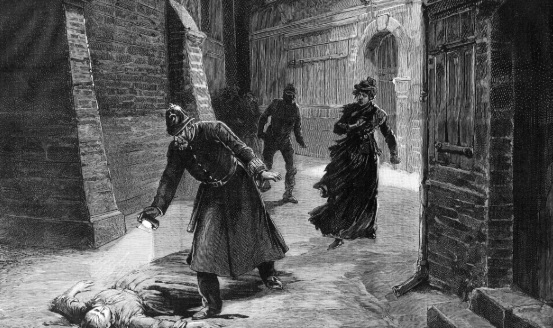

The Whitechapel Murders: A Bloody Chronicle of Terror

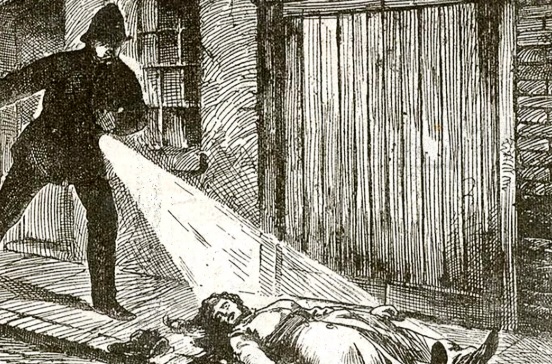

The Whitechapel Murders, committed in the late summer and fall of 1888, stand as some of the most chilling and grotesque crimes in history. The murders left a trail of brutality that still haunts us today. The first victim, Mary Ann Nichols, was discovered on the morning of Friday, August 31, 1888. Her throat was severed and her abdomen violently ripped open.

Just over a week later, on Saturday, September 8, Annie Chapman was found in a similarly gruesome state. Her throat was slit and her abdomen mutilated—her internal organs callously removed. The horrors escalated on the night of September 30, when Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were killed within hours of each other. Stride’s throat was slashed, while Eddowes endured the same fate. Her face disfigured and her organs removed in a grotesque display of savagery.

The final victim of Jack the Ripper, Mary Jane Kelly, was discovered on Friday, November 9, in the privacy of her bed. Her murder was by far the most horrific. Her face mutilated, her throat slashed, and her internal organs removed. To add to the nightmare, her heart was missing, leaving behind a chilling message of violence and depravity. These five murders have made the Whitechapel killings a dark chapter in criminal history.

The Suspects: A Cast of Characters in the Ripper Mystery

Over the years, the identity of Jack the Ripper has sparked endless speculation. Numerous suspects continue to emerge from the shadows of history. One of the most popular candidates is Aaron Kosminski. Kosminski was a Jewish Polish man who was admitted to the Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in 1891.

Kosminski was said to suffer from auditory hallucinations and a paranoid fear of being fed by others. He also refused to bathe and had a history of self-abuse. His background and heritage led some to suggest that he could explain the cryptic graffiti found on a wall near one of the victims. The message read, “The Jews are not the men that will be blamed for nothing.”

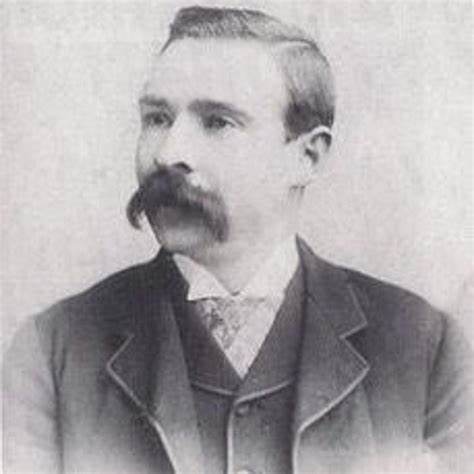

Another intriguing figure is Francis Tumblety, an American in London during the murders and quickly became a serious suspect. Tumblety’s life was filled with controversy, from his criminal activities to his bizarre obsession with female anatomy. At a dinner party, he reportedly boasted about his collection of uteruses. And Tumblety’s hatred of women and prostitutes was well known.

Tumblety’s history of criminal behavior, including a potential link to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, only added to his chilling profile. He fled London in 1888 after being implicated in homosexual acts and returned to the U.S. There, he reinvented himself as a snake oil salesman.

The Famous & Most Outlandish Jack the Ripper Suspects

The most sensational suspect is Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale. His name has been linked to the murders due to royal scandal. One theory suggests the Duke embarked on a killing spree to seek revenge on prostitutes who gave him syphilis.

However, it was later proven that Prince Albert did not have syphilis and had solid alibis. The story then morphed into a wild narrative of secret marriages and a child born to an ex-prostitute. According to this theory, the child was a potential threat to the throne. This theory prompted Queen Victoria and her Freemason allies to orchestrate a brutal cover-up. And, of course, they had to silence anyone who knew about the child. While this theory is widely dismissed, its intrigue endures.

Perhaps the most bizarre suspect is Lewis Carroll, the famous author of Alice in Wonderland. Some conspiracy theorists have suggested that Carroll’s work was based on a secret child of Prince Albert. They say clues about the Ripper’s identity are hidden within his novels. One particular claim centers around Carroll’s diary entries, which were supposedly written in purple ink. However, on the nights of the Ripper murders, all entries were written in black. This, of course, is presented as the “damning” evidence of his guilt. Other than this, the connection between Carroll and the Ripper remains purely speculative.

Then, in November 1888, the murders suddenly ceased, without explanation. One month later, the body of the missing Montague Druitt was discovered floating in the River Thames. His death added another layer of mystery to the case. Could Druitt have been connected to the Ripper’s gruesome killing spree? And if so, what role did his death play in the story of Jack the Ripper? The mystery deepens.

The Facts Regarding the Death of Montague Druitt: A Mystery Unraveled

Montague Druitt’s life took a sharp, dark turn in late 1888. On Friday, November 30, his position as a master at the Blackheath School for Boys was abruptly terminated. His superior, George Valentine, told Druitt’s older brother, William, that Montague had been let go due to “some trouble.” He offered no further explanation, leaving the reason shrouded in ambiguity. The mystery deepened when, in December, Montague was also removed from his role as treasurer of the Blackheath Cricket Club. The club’s minutes simply stated that it was assumed Montague had “gone abroad.”

Montague’s sudden and unexplained disappearance remained unsolved until December 31. That was when his body was discovered floating in the Thames River on New Year’s Eve. A waterman named Henry Wisdale found him near Thornycroft’s torpedo works. It became quickly apparent that the body had been submerged for over a month. Druitt was weighed down by stones placed in his pockets.

Upon further inspection, a train ticket to Hammersmith dated December 1 was found on Montague’s person. He also possessed a silver watch, a check for 50 pounds (roughly $7,750 in today’s money), and 16 pounds in gold (around $2,500 today). The discovery raised several disturbing questions. Where was Montague Druitt planning to go with over $10,000 in his pockets? Why had he been in such a hurry to leave, only to end up dead in the Thames?

These unanswered questions would soon be overshadowed by the Cleveland Street Scandal that erupted in the new year. That event might hold the key to understanding Montague Druitt’s tragic end.

The Cleveland Street Scandal: A Dark Web of Secrets and Scandal

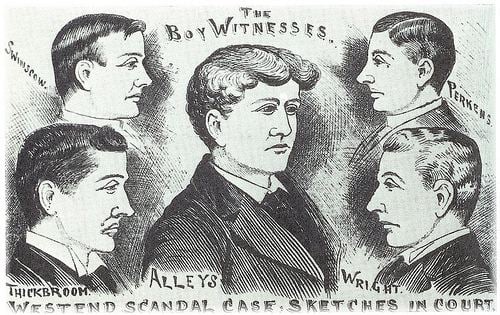

The Cleveland Street Scandal surprised the public and sent shockwaves through London’s high society. It started with a petty theft investigation involving 15-year-old General Post Office telegraph boy Charles Thomas Swinscow. Police investigated how the young boy came into possession of about $75. They soon uncovered a much larger and far more sinister operation: a male homosexual brothel.

Homosexuality had been illegal in England since 1533. And it wasn’t until the 1863 Offenses Against Persons Act that sodomy was no longer punishable by death by hanging. In the late 19th century, any gentleman who preferred the company of other men to women had to be extremely discreet. Otherwise, he ran the risk being imprisoned—or worse. During the investigation, young Charles confessed that he and two fellow teenage telegraph boys worked as prostitutes at the Cleveland Street brothel. In their confession, they outed a man named Charles Hammond.

The case was handed over to Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline. Yes, the very same Abberline who investigated the Jack the Ripper case. Under Abberline’s orders, the brothel was eventually shut down. Hammond was arrested, and the men involved were prosecuted under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1865. That act made homosexual acts punishable by two years in prison. While the punishment wasn’t as severe as hanging, the resulting public shame was often equally devastating.

More Jack the Ripper Connections to Literature & Royalty

The scandal grew more sensational as it was revealed that several prominent individuals had frequented the brothel. The biggest name of the sting was renowned poet and playwright Oscar Wilde. And one of the most explosive revelations was the involvement of Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale. Yes, the royal figure often linked to the Jack the Ripper murders.

Among the other implicated figures was Lord Arthur Somerset, the personal head of stables to Prince Albert Victor. Somerset was repeatedly named in connection with the brothel but still managed to escape prison time. He fled to France, where he lived out his life. Somerset is believed to have helped others implicated in the scandal flee the country. He is said to have often provided cash and train tickets. Another suspect, George Veck, had been arrested at London Waterloo railway station with incriminating letters in his possession. His letters detailed romantic entanglements with other men.

As the scandal unfolded, attention turned to Francis Tumblety, the American suspect previously tied to the Ripper case. Tumblety was arrested in November 1888 for gross indecency after being caught engaging in homosexual acts. While in jail, Tumblety became one of Scotland Yard’s primary suspects in the Ripper case. He eventually managed to escape custody, sneaking into France under the name Frank Townsend. From France, Tumblety returned to the United States and continued his life as a fraudulent snake oil salesman.

But perhaps the most intriguing connection in the Cleveland Street scandal was the mention of Montague Druitt. The name that surfaced in the investigation of the Jack the Ripper murders now echoed through the dark corridors of this notorious scandal. The news further deepened the mystery surrounding Montague’s death.

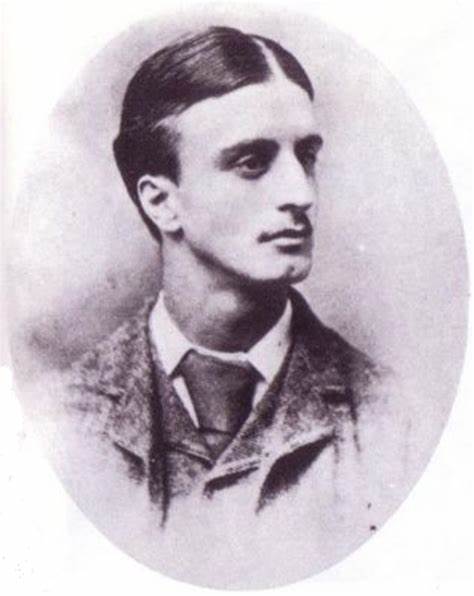

The Life of Montague Druitt: A Tragic Tale of Promise and Despair

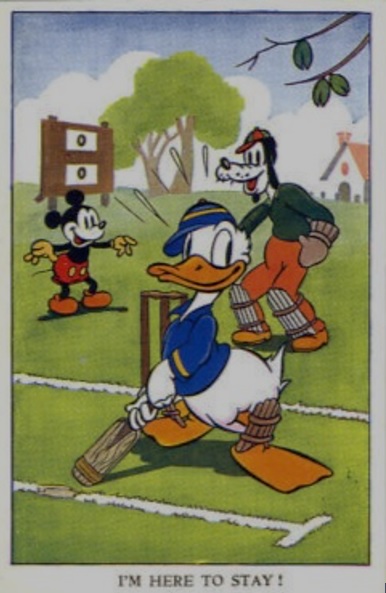

Montague Druitt was a man of many talents, known primarily for his cricketing prowess. As a lifelong cricketer, he earned a reputation as an outstanding bowler. Druitt played for clubs such as the Kingston Park Cricket Club and Dorset County Cricket Club. His skills even took him on a tour of the West Country with the ironically named touring team, the “Incogniti.”

Druitt’s impressive career included several remarkable feats, such as taking multiple ducks from prominent players. He also collected numerous wickets, including a legendary “fiver” in one match. His dedication to the sport was so strong that just months before his death, Druitt was still playing for Blackheath. In 1884, Druitt’s hard work and skill earned him a coveted place in the prestigious Marylebone Cricket Club.

Who Was Montague Druitt if Not Jack the Ripper?

Born the son of a prominent doctor, Montague was well-regarded in London society. However, his life took a tragic turn in 1885 when his father suddenly died of a heart attack. The loss strained the Druitt family. Montague’s mother, Ann, struggled with mental illness in the wake of this trauma. Some conspiracy theorists point to a curious connection between Montague’s mother and Annie Crook.

It is claimed that both women were in the same asylum. Annie’s daughter Alice, the alleged illegitimate child of Prince Albert, was also sometimes cared for by Ripper victim Mary Kelly. While such theories are speculative at best, they do add an eerie layer to Montague’s life story.

A Sadness Dealing with Tragedy

Mental illness ran deep in the Druitt family. Both Montague’s grandmother and his eldest sister, Georgiana, tragically took their own lives. Georgiana jumped from a top-floor window, and Montague’s mother later spent time in a sanitarium, plagued by suicidal tendencies and delusions. Montague, while deeply affected by these family tragedies, built a career for himself as a barrister by day, and a teacher at Blackheath Boys School by night, balancing his professional life with his passion for cricket.

Despite his accomplishments, Montague never married and there are no records suggesting that he had romantic relationships. His private life, it seems, was as mysterious as his tragic end. In the aftermath of his strange disappearance in late 1888, Montague’s brother, William, discovered an unsettling note addressed to him, written by Montague. The note read: “Since Friday I felt that I was going to be like mother. And the best thing for me was to die.” The “Friday” Montague referred to was the day he was fired from Blackheath Boys School, a pivotal moment that may have led to his descent into despair.

The circumstances surrounding Montague’s death remain a source of intrigue. A supposed suicide note, combined with his mental health history, suggests he may have taken his own life. Yet, there are several questions that remain unanswered. Montague was known to be an accomplished swimmer, which makes it odd that he would have chosen to drown himself in the Thames. Was it truly a suicide, or was there something more sinister at play? The mystery of Montague Druitt’s death remains unsolved, leaving us to wonder whether his tragic end was a result of his own despair or the darker forces that may have been involved.

How Montague Druitt Became a Suspect: The Dark Rumors and the Truth Behind the Allegations

Rumors had been swirling for years within London’s social elite, and the whispers grew louder when Montague Druitt was linked to the infamous Jack the Ripper murders. Those who knew him or were connected to him through his prestigious Oxford education and legal work began to speculate that the quiet, respectable man could also be the city’s most notorious killer.

It became, in the words of some, London’s worst-kept secret that Montague Druitt was indeed the Whitechapel killer. The allegations took a more official turn on February 23, 1894, when Assistant Chief Constable Sir Melville Macnaghten submitted a private handwritten memorandum making Montague Druitt a primary suspect. In his memorandum, Macnaghten stated that he had received “private information” that left him with “little doubt” regarding Druitt’s guilt.

This assertion was particularly shocking as Macnaghten claimed that even Montague’s own family believed him to be the Ripper. This raised the question: Was it this “trouble” that Montague was trying to escape when he took his life—or did he meet a different, more sinister fate?

Spreading Jack the Ripper Rumors & Allegations

The whispers didn’t stop there. In 1891, Sir Henry Richard Farquharson, a prominent member of government and high society, confidently boasted that he knew the identity of Jack the Ripper and claimed it was “the son of a surgeon”—Montague Druitt. According to Farquharson, Druitt had taken his own life in order to escape justice.

Adding fuel to the fire, an Australian pamphlet titled The East End Murderer – I Knew Him was allegedly published by Montague’s cousin, Lionel. This pamphlet purportedly revealed information confirming Montague’s guilt. However, despite many attempts to locate copies of this pamphlet, none were ever found, leaving the claims to linger in the realm of hearsay.

Macnaghten, who had taken over the police force in 1889, just after the Ripper murders, asserted that Druitt was of an “unsound mind” and even described him as “sexually insane,” suggesting a possible link between Montague’s alleged mental health issues and the brutal crimes. But what exactly was the evidence that led Macnaghten to make such bold claims?

And why did authorities, despite the discovery of Montague’s body with a train ticket and $10,000 on him, assume he had committed suicide? The answers remain shrouded in mystery, adding layers of complexity to the already enigmatic life and death of Montague Druitt, leaving open the question of whether he was indeed Jack the Ripper or just another victim of cruel fate.

The False Evidence: A Look at the Real Jack the Ripper Suspect

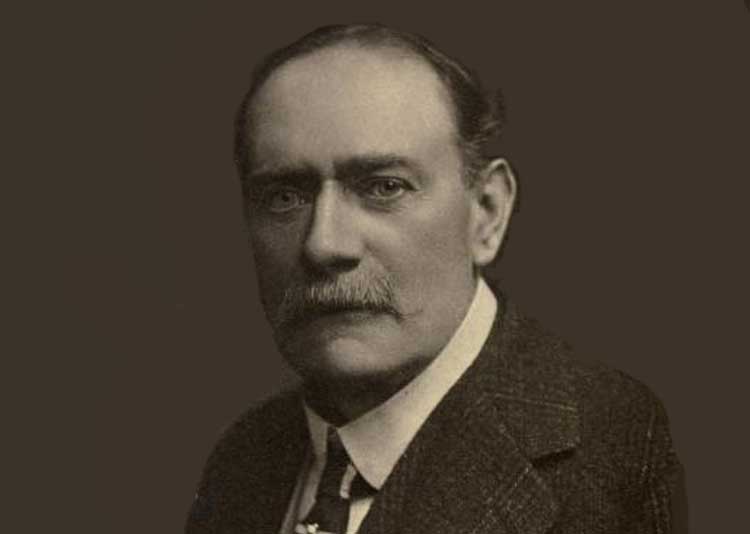

The infamous Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline, renowned for his work on the Cleveland Street Scandal, was the first detective to work the Jack the Ripper case from the very first victim until his promotion near the end of the investigation. As the authority on the case, Abberline had a keen insight into the Ripper’s crimes and, notably, never considered Montague Druitt as a serious suspect.

Instead, his prime suspect was a man named Severin Antoniovich Klosowski, better known by his alias George Chapman. Klosowski was a sinister-looking individual, with deep, unnerving eyes and a handlebar mustache that seemed to suggest he belonged in a crime novel. His unsettling appearance only added to his disturbing background.

Chapman operated a musical barbershop with his girlfriend, where she played the piano while he serenaded customers and gave them haircuts. However, his dark tendencies emerged when he killed her by poisoning. He continued this deadly pattern with subsequent girlfriends, poisoning them as well, before moving on to run a new bar in a new town. His crimes continued until he was eventually caught and hanged for murder in 1903. Incredibly, his wife – who somehow survived the entire ordeal – remarried just a month after his execution.

Chapman, who had also attempted to strangle and behead his wife with a knife he hid under their bedroom pillow, was linked to multiple other violent acts, including a murder in New York City. And while there was a rumor that he was seen with Mary Kelly on the night she was murdered, it’s important to note that Chapman left for America shortly after, coincidentally around the time when the Ripper killings ceased.

Another Popular Suspect

Another prime suspect for Abberline was a Polish barber and hairdresser named Aaron Kosminski. Kosminski was often connected to the murders based on DNA evidence found at one of the crime scenes, but at the time, Abberline lacked the necessary proof to arrest either Chapman or Kosminski. Kosminski eventually died in a mental institution in 1919. In fact, Abberline’s note on the investigation suggests that Montague Druitt was only considered a suspect because of the inconvenient timing of his death, which coincided with the end of the Whitechapel murders.

There are several reasons Montague Druitt didn’t fit the description of the Ripper. He didn’t match any of the witness descriptions, and he wasn’t frequently in the area, especially at night when the murders occurred. Despite his connection to London’s legal and academic circles, Druitt was often busy with his job as a night teacher and his daytime work as a barrister. His personal time was dedicated to cricket, which placed him far away from Whitechapel during the times of the murders. For instance, Druitt was playing cricket in Dorset the day after Mary Ann Nichols was murdered, and he was playing for Blackheath on the morning Annie Chapman’s body was discovered.

Given all of this, it raises the question: If Montague Druitt was not Jack the Ripper, then what drove him to his mysterious death in November 1888? The answer remains elusive, as Druitt’s tragic end continues to perplex investigators and conspiracy theorists alike.

My Final Conclusions: The Tragic Death of Montague Druitt

Over the years, much speculation has arisen about why Montague Druitt took his own life. Some have even suggested he was murdered, but I believe there is a simpler, sadder explanation for his death. The large sum of money he had on him at the time of his death can be reasonably explained.

Montague was likely given his severance pay when he was terminated from his teaching position, and that explains the check he was carrying. As for the train ticket found on him, it was merely a transfer ticket, something necessary for his journey since the station from which he left required a change. Regardless of whether he intended to go home or end his life, Montague would have needed that ticket for his transfer.

There is a strong theory that Montague was homosexual, a claim based on his bachelor lifestyle and connections to known figures involved in underground homosexual circles of the time. It’s likely that Montague was outed, which, in a society where homosexuality was criminalized and socially condemned, would have caused him immense shame.

His respectable status would have likely afforded him some means to escape the situation – perhaps with financial assistance from someone like Lord Somerset, who may have provided him with the money and ticket to leave London, possibly to avoid an arrest or public scandal related to his sexual orientation.

A Good Man Ridiculed for His Identity

Even his cricket club appeared to cover for him. The minutes from the club, just after his disappearance, stated that Montague had “gone abroad,” suggesting that those close to him may have known of his plan to flee. The clubmates who later learned of his death never once indicated that they suspected he had committed suicide; instead, they believed he was simply out of the country.

Ultimately, I believe that Montague, in a moment of loneliness and overwhelming depression, chose to end his life on a cold November night. Perhaps he was driven by a deep sense of shame about his sexual identity and a desire to spare his family from the humiliation that might come with the revelation of his homosexuality.

Montague, knowing the tragic history of his family – where mental illness had claimed the lives of both his sister and his mother – was likely terrified of following the same path. From his legal training and understanding of his society, he knew that suicide was a crime, and families often had to pay the price for it. Therefore, he may have intentionally feigned insanity, ensuring that his death was seen as the act of a troubled mind, thus sparing his family from further shame and responsibility.

Montague Druitt was not murdered, and he was certainly not a killer himself. He was a victim of a society that couldn’t understand him, a man of deep character and complexity, who was never afforded the freedom to be who he truly was. His death, like many of the tragic lives around him, was shaped by the oppressive norms of his time. And as for the identity of Jack the Ripper? The case remains open, but I am convinced that Montague Druitt’s tragic fate should not be clouded by false accusations.

Listen to Our True Crime Podcast ‘Deadly Overs: A Podcast of Murder & Cricket’

Learn about another infamous Deadly Overs true crime story: The Dominatrix and the Dead Umpire.